💎 The Cullinan Diamond

The Greatest Gem Ever Found

Few stories in jewellery history capture the imagination quite like that of the Cullinan Diamond — the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever discovered. Weighing an astonishing 3,106.75 carats, this stone was found at the Premier No.2 mine in Cullinan, South Africa, on 26 January 1905.

At first, no one knew quite what to do with it. The diamond’s sheer size made it almost unbelievable — some even thought it was a crystal of quartz. But as news spread, the world’s fascination grew.

From Mine to Monarch

In April 1905, the Cullinan was sent to London for sale. Despite enormous interest, it remained unsold for nearly two years. Finally, in 1907, the Transvaal Colony government decided to purchase the diamond and present it as a gift to King Edward VII of the United Kingdom — a gesture of loyalty and goodwill.

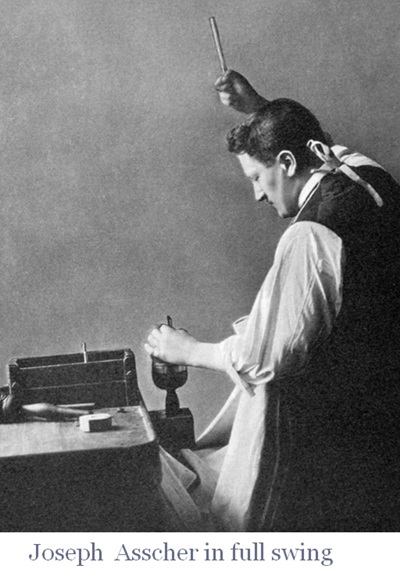

The King entrusted the legendary Joseph Asscher & Co. of Amsterdam with the daunting task of cutting and polishing the rough stone into a collection of finished gems.

The Journey to Amsterdam

In a story fit for a spy novel, Abraham Asscher personally travelled to London to collect the diamond from the Colonial Office on 23 January 1908. He simply slipped the priceless gem into his coat pocket and boarded a train and ferry back to the Netherlands.

Meanwhile, to throw off would-be thieves, a Royal Navy ship sailed across the North Sea carrying an empty box under heavy guard — even the captain didn’t know that his “precious cargo” was a decoy.

The Cut of a Lifetime

On 10 February 1908, Joseph Asscher prepared to cleave the Cullinan at his diamond-cutting factory in Amsterdam. The process was nerve-racking — no one had ever attempted to cut a diamond of that size, and there was no technology to guarantee success.

Asscher spent weeks studying the stone, mapping out its internal planes and flaws. He finally made an incision half an inch deep (1.3 cm) to guide the split — a task that alone took four days.

On the first attempt, the steel knife snapped. The second blow, however, struck perfectly — the diamond split cleanly in two along one of its natural cleavage planes.

From there, the work continued for eight months, with three craftsmen labouring 14 hours a day to cut and polish the fragments into brilliant gems of various sizes and shapes.

Legend or Truth?

The dramatic moment of the split has inspired many retellings. In his book Diamond: A Journey to the Heart of an Obsession (2002), Matthew Hart wrote that Joseph Asscher was so overcome with tension that he had a doctor and nurse on standby — and fainted immediately after striking the diamond.

However, Lord Ian Balfour, author of Famous Diamonds (2009), suggests otherwise. He believes Asscher likely celebrated the success with a bottle of champagne instead.

Asscher’s nephew Louis later dismissed the fainting myth altogether, declaring:

“No Asscher would ever faint over any operation on any diamond.”

A Legacy in Light

The Cullinan Diamond produced nine major stones and ninety-six smaller brilliants, including the Great Star of Africa (Cullinan I) — the 530.2-carat pear-shaped diamond that remains the largest cut diamond in the world.

Today, several of these stones are set in the British Crown Jewels, symbols of craftsmanship and courage — and a reminder of the human skill behind nature’s most breathtaking creation.

When I started Jewellery Training Solutions, my goal was simple — to make professional trade-level jewellery education accessible anywhere in the world.This year, that goal came to life on a global scale. The JTS Teaching Tour 2025 took me from the southern hemisphere to the northern, meeting jewellers, students, and educators who share the same passion for craftsmanship and skill development.

When I started Jewellery Training Solutions, my goal was simple — to make professional trade-level jewellery education accessible anywhere in the world.This year, that goal came to life on a global scale. The JTS Teaching Tour 2025 took me from the southern hemisphere to the northern, meeting jewellers, students, and educators who share the same passion for craftsmanship and skill development.